The Haggerston Nobody Knows February 16, 2013 by William Palin With the Geffrye Museum planning to demolish the Marquis of Lansdowne - one of the few remaining fragments of nineteenth century Haggerston – William Palin recalls the lost wonders of this once coherent and distinctive neighbourhood.

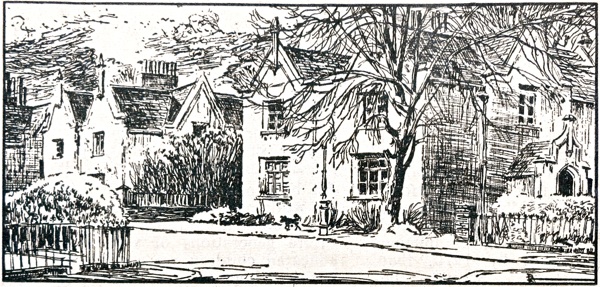

Tudor Gothic Villas in Nichols Sq, 1945

Haggerston, in the Borough of Hackney, remains one of those ‘lost’ districts of London’s inner suburbs. Even the boundaries of this elusive locale have fluctuated, yet although the current electoral ward extends deep into Shoreditch, I would draw the borders of Haggerston at Hackney Rd to the south, Queensbridge Rd to the east, Kingsland Rd to the west and Regent’s Canal to the north.

Just a few important public buildings remain in Haggerston, including the old Haggerston Library - which was left to rot in the seventies before being facaded in the nineties – and the magnificent Haggerston Baths on Whiston St with its gilded Golden Hind weather vane. Poignant indicators of the glories that once were here.

Although Haggerston suffered some bomb damage – St Mary’s Church by John Nash was completely destroyed in 1941 – it was the post-war planners who erased most of the superior nineteenth century terraces, with streets of sound houses succumbing to the bulldozers as late as 1978. While the estates that replaced them may have provided superior accommodation and new amenities, they were brutal and uncompromising in their disregard for the intimacy, cohesion, humanity and community spirit of the old streets - attributes embraced in other similar London neighbourhoods wherever the terraces were retained.

As London’s population grew rapidly in the nineteenth century, Haggerston became a densely populated industrial suburb. In many eastern districts, land ownership tended to be fragmented, resulting in a series of relatively small-scale building speculations that eventually came together to form a coherent if quirky network of streets with pubs, shops and small industry, all adding to the diverse character of the streetscape. Although individual speculators – whether a few houses or a whole street – imposed a uniformity of design, there was surprising and delightful variation between streets with even modest houses exhibiting decorative flourishes in their brickwork, fanlights, shutters and front doors. Where streets met, the junctions were resolved with an effortless dexterity which was one of the striking characteristics of the London speculative builder and, on the rare occasion a pub was absent, a corner house was built with a side entrance.

In common with most of south Hackney and Shoreditch, the dominant industries of the area were the furniture and finishing trades. An insurance map of 1930 shows timber yards, French polishers, enamellers, cabinet factories, mirror frame factories, wood carvers and a plethora of other related trades. Interestingly, the legacy of these industries is still evident today in the Hackney Rd, where Maurice Franklin the ninety-three year old wood turner works at The Spindle Shop and D.J.Simons maintain their thriving business supplying mouldings for picture framing after more than a century, as well as in the handful of second hand shops trading in the furniture once made locally.

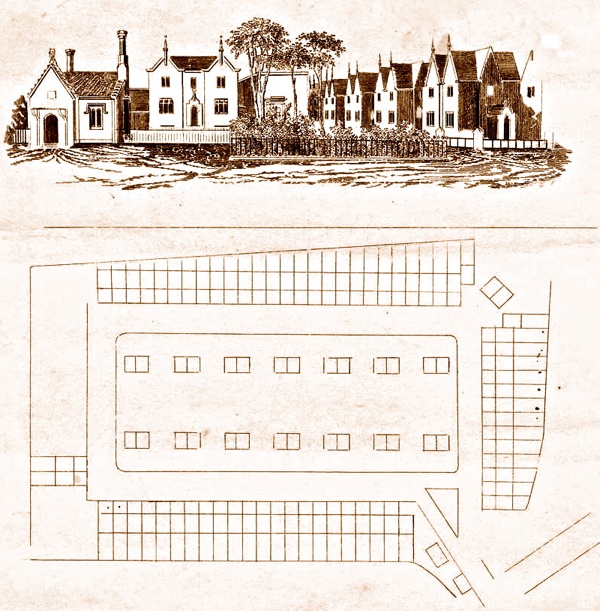

Unquestionably, the centrepiece of Haggerston’s nineteenth century development was Nichols Sq, situated east of the Geffrye Museum beyond the railway viaduct. Built in 1841 and featuring two outward facing rows of picturesque Tudor gothic villas at its centre, Nichols Sq was further enhanced in 1867-9 by a splendid church and vicarage – St Chad’s – by the architect James Brooks. Surviving in good condition until blighted by a Compulsory Purchase Order, the square was swept away in 1963 for the Fellows Court Estate. Geoffrey Fletcher, author of ‘The London Nobody Knows,’ lamented the impending loss in 1962 by illustrating the houses in the Daily Telegraph, and describing “the delightful Gothic villas … in excellent condition [which] if they were in Chelsea would fetch anything from £10,000 to £15,000.” Savouring the architectural detail, he comments “Typical of the finesse of the period is that, while the terrace railings have a Classic flavour, the similar ones of the cottages have a Tudor outline. But after next year none of this will matter any more.”

The London County Council planning files record no evidence of any robust defence of Nichols Sq. The principal concern – ironic in the context of the current plans to demolish the Marquis of Lansdowne pub – was the effect of the new tower blocks upon the setting of the Geffrye Museum. Nichols Sq had only one entrance, which led from Hackney Rd at the south east corner, and this was guarded by a Tudor lodge. The secluded location had helped it retain an isolated respectability until the very end, despite the incursion of the railway viaduct across its western extremity just a few years after completion.

To the south of Fellows Court Estate is Cremer St, the only direct link between Hackney Rd and Kingsland Rd, which was once graced by a series of modest but elegant semi-detached villas (a building type that became a defining characteristic of Hackney). These villas are captured in a beautiful series of LCC photographs of 1946, which also show a double-fronted detached house with a wide fanlight, where an old man perches on the high front steps, lighting a pipe. In Cremer St, The Flying Scud pub, with its distinctive blue Truman’s livery survived until only a few years ago, while running south from there – now reached via a rubbish-strewn alley – is Long St, whose distinctive yellow brick houses are also illustrated in the LLC old photographs. Of these, only a few paving stones survive.

To the north of the Fellows Court Estate is Dunloe Street, once lined by neat terraces, now bleak save for St Chad’s Church – the last fragment of Nichols Sq. Dunloe St linked into a network of small streets, including Appleby St and Ormsby St, where well-maintained and well-loved terraces endured until 1978 when they were controversially emptied of their occupants and demolished. A handful of houses on the west end of Pearson St are now the only reminders we have of this once vibrant and homogenous neighbourhood.

In 1966, architectural critic Ian Nairn spoke eloquently of the lost opportunities of the rebuilding of the East End, in words that perfectly describe the fate of old Haggerston - “All the raucous, homely places go and are replaced by well-designed estates which would fit a New Town but are hopelessly out of place here. This is a hive of individualists, and the last place to be subjected to this kind of large-scale planning. Fragments survive, and the East Enders are irrepressible …but they could have had so much more, so easily.”

The tragedy is that fifty years on from the loss of Nichols Sq the destruction still continues. The only remaining building from the eighteen thirties on Cremer St is the Marquis of Lansdowne pub. It is owned by the Geffrye Museum, an institution that exists to foster an understanding of the history of domestic design, furniture and the culture of ‘the home.’ Astonishingly, the Geffrye wants to demolish it for a new extension. Perhaps the trustees need a walking tour and a history lesson? After all the needless destruction that has been enacted upon its doorstep, if even a museum cannot learn from history what hope is there?

Submit an objection to the demolition of the Marquis of Lansdowne direct to the Borough of Hackney by clicking here and entering the application number 2013/0053. The more objections the council receives the more likely it will refuse this application.

Alternatively, you can send your objection as an email to planning@hackney.gov.uk quoting application number 2013/0053 or send a written objection to Planning Duty Desk, Hackney Service Centre, 1 Hillman Street, E8 1DY.

Weymouth Terrace shortly before demolition, 1964. Note the stuccoed ground floor facade

Top